With a new way of looking at how we teach, one that is evidence-based and embedded in student learning progress, teacher communities are positioned to make powerful and informed decisions about teaching pedagogy.

In Part 1 of our series, Towards collective teacher efficacy, we considered the construct of building relational trust as fundamental to any success in achieving sustained and improved student learning outcomes. Whilst researching for the article, Without relational trust, innovation is lost, it became abundantly clear that without genuine trust, and the commitment and collaboration that it fosters amongst leaders and teachers alike, the likelihood of improvement and teaching innovation were slim.

It is believed that Albert Einstein once said, ‘the definition of insanity is to do the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result’. These words, whilst simple, are quite profound when considered in an educational context, and motivate teachers and leaders to reflect deeply about their level of impact on student learning, often in ways that have not been done before. To do this, a community of deep learners needs to evolve within the school, one that activates collective teacher efficacy (effect size 1.57) and the shared belief that by working together improved outcomes can be attained by all learners.

Unfortunately, and often by choice, many teachers continue to find themselves isolated from their peers, not necessarily socially, but professionally. This is no surprise given the level of risk and emotion associated with opening yourself up to the process of collaboratively analysing your impact on student learning with peers. For this reason, relational trust must be skilfully established by leaders, and then nurtured, before proceeding with the development of Professional Learning Communities (PLCs).

The vast majority of teachers are proud and hardworking, and regardless of their current level of impact, this should not be forgotten. Rather than making judgements, the view of a learning organisation should be adopted at all levels of a school where everyone has something new to learn; something that may well make a difference for students. Only then can teachers have the type of dialogue that supports the deep, respectful and professionally critical analysis of how they teach. Under these conditions, and embedded in collaboration and evidence, teachers are empowered as they begin to move from good to great, and from experienced to expert.

Richard Elmore in Building a New Structure for School Leadership (2000) asserts that ‘the key barrier to successfully and dramatically improving student performance is that too many teachers are isolated and have little opportunity for professional collaboration with colleagues.’ These teachers lack the robust and productive dialogue that underpins an effective PLC. Under such professionally isolated conditions, the status quo of ‘best intention but limited impact’ often prevails, as teachers continue to engage with the same strategies year after year without the skills, collegiate support or motivation to identify their effectiveness, and change their teaching approach when instances of minimal impact are identified.

Committed to making a difference for all learners, high impact leaders seek to challenge this status quo in a way which is collaborative, and teacher driven, through the establishment and development of PLCs. For many schools, and leadership teams, this increasingly means the identification and engagement with systems and protocols that will support teachers to collaboratively reflect on the impact of their teaching on student learning.

Let’s take a step back for a minute and consider the evolution of PLCs. They have been present in schools, particularly the U.S. since the 1960s, however their purpose and structure has evolved considerably in line with an increase in evidence-based research on the impact of different PLC models in the 1980s. Traditionally, the focus of PLCs was on teaching, and more often than not, the telling of war stories to get a laugh. Many of these meetings were founded on a deficit model where learning success was viewed as the responsibility of the student, rather than the teacher and school. In this culture, the view that some students simply could not be taught was perpetuated, and subsequently, learners that needed quality teachers most, fell through the cracks.

Fortunately, this culture, and the beliefs that it supports, are increasingly uncommon in education today. The modern PLC is focused on identifying the impact of current teaching strategies on student learning, and then using this knowledge to inform future teaching innovations, as part of an ongoing cycle of teacher development. Hattie’s research in What works best in education: The politics of distraction (2015) identified that teachers working together to evaluate their impact has an effect size of 0.93. An effect size of this magnitude is rare making the development of systems that support teachers to work together to evaluate their impact a school priority worth pursuing.

Hattie also asserts that “when the collaboration within PLCs is based on learning from errors, seeking feedback about progress and enjoying going into the ‘learning pit’ together with expert help that provides safety nets, and guidance out of the pit, teacher development and student learning outcomes are accelerated”. Once this process is established, and PLCs become increasingly autonomous, teacher engagement with high impact teaching strategies is fast-tracked.

Making teacher impact clear, together

Fundamentally, an effective PLC generates and analyses evidence of the impact of teaching strategies that are being used. With this new way of looking at how they teach, one that is evidence-based and embedded in student learning progress, teachers are positioned to make powerful and informed decisions about teaching pedagogy. Just as importantly, they are decisions that are not made in isolation but with the input, experience and ongoing support of colleagues who find themselves in the same position: trying to achieve PROGRESS FOR ALL, All of the time.

Gallimore and Ermeling in Five Keys to Effective Teacher Learning Teams (2010), have synthesised the drivers of a successful PLC. “It’s not just meeting as a team that makes the difference. Rather, it is how the teams use the time that is set aside to gradually and steadily improve lessons and instruction. Year level like teams, peer facilitators, protocols, and stable settings create focused opportunities and build teachers’ confidence that their efforts are paying off for their students. When that kind of work is sustained and supported, the promise of teacher collaboration is translated into achievement results.” Infographic 1 captures the five aspects of high performing PLCs and provides school leaders with a guide to the systems and processes necessary for teachers to regularly reflect on student learning and teaching impact. This sees educators focusing first on learning, before turning their attention to teaching.

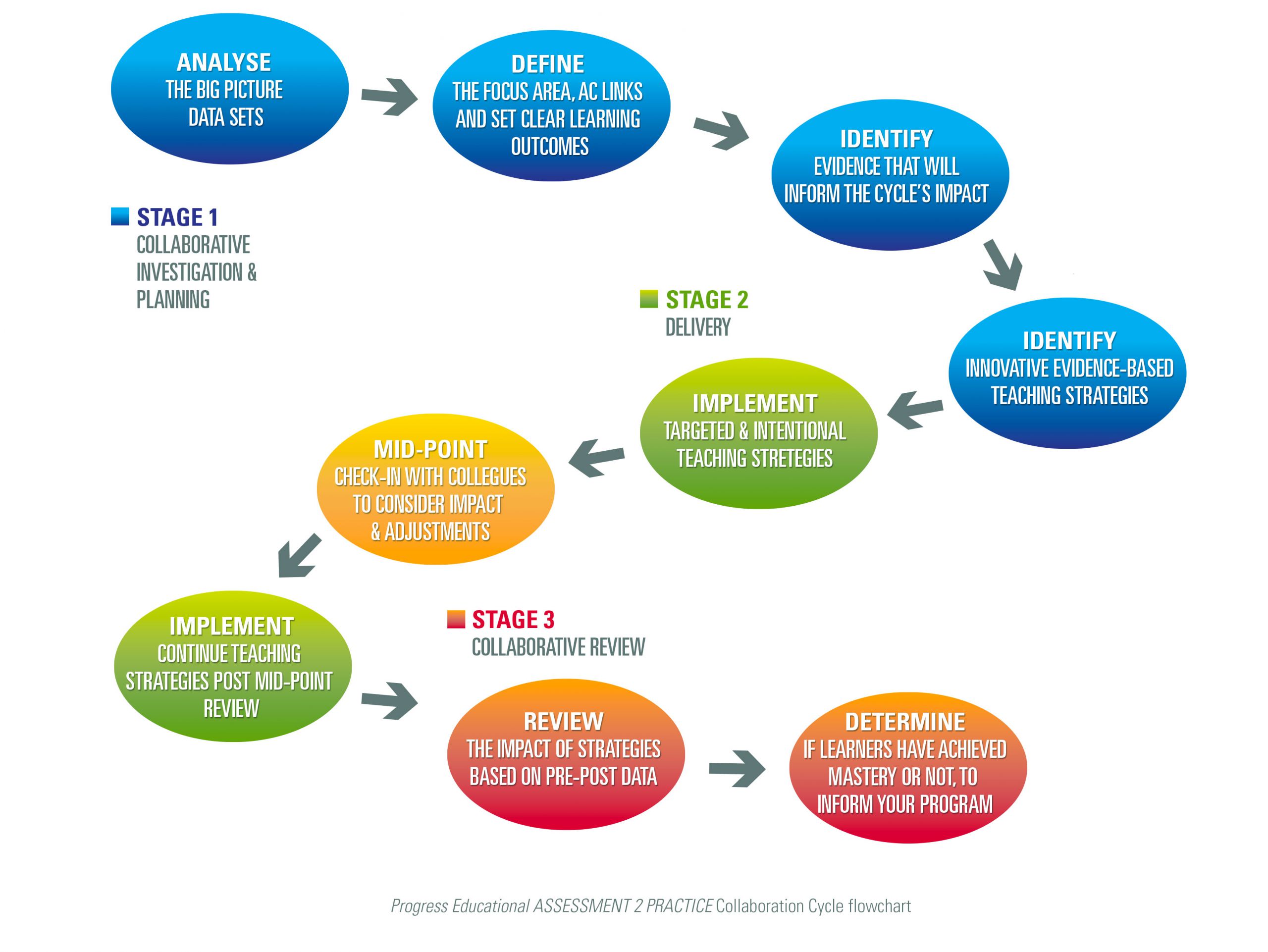

When leaders provide regular, protocol guided opportunities for teacher teams to focus on the impact of their teaching, individual teachers, and the learning communities that they are a part of, are in a position to translate this new knowledge into more effective teaching. Acutely aware of the importance of this I have developed the ASSESSMENT 2 PRACTICE Collaboration Cycle, a protocol that guides teacher teams through each stage of the collaborative teacher impact analysis process. Over time, and with the ongoing and committed support of leadership through resourcing and participation, this inquiry into teaching impact becomes a driver for teacher development and school improvement.

So, in summing up, if collective teacher efficacy is about teams working towards shared goals, then a high functioning, protocol guided Professional Learning Community is the ‘horse that pulls the cart’ of teaching impact analysis and improved student learning. When teachers come together and pool their knowledge of effective teaching in a collaborative approach to planning, implementing and analysing teaching strategy impact, schools become true learning organisations. Organisations where teachers learn from, with and for one another, where evidence of learning directs teaching strategy choice and where student learning success is central to all decision making.

Have a question for Travis, or need more info? Let’s chat.

Under no obligation, our preference is to spend time with you prior to delivering professional learning for teachers, or tailored leadership guidance, so that the partnership we develop is unique to your school.

When pursuing PROGRESS FOR ALL, All of the time, we believe time spent planning is time well spent.