“…one of the major reasons why change does not lead to improvement, is that there is too much focus on future practice, and not enough on the forces that explain and sustain current practice…”

(Robinson, 2017)

Viviane Robinson, in Reducing change to increase improvement (2017), promotes a new paradigm of change. She challenges the endless pursuit of change, questioning whether this change actually makes a difference to student learning outcomes. Instead, she believes “…it is time to stop talking about change and innovation and to focus on the far more ambitious goal of achieving improvement”.

Formal improvement planning is a given in modern education. What is not a given is if all those plans, goals, targets and intended outcomes are achieved. Do we actually make a difference to student learning outcomes, the core business of any successful learning organisation? More often than not these plans fail to leave the school, and more importantly learners, better positioned than they were in the first place. This is in spite of the best intentions of leaders and teachers, careful planning and collaboration, engaging with educational research and the extensive resourcing that is necessary to support teacher development.

The challenge for leaders is to engage educators in a dialogic process that will see teaching innovations become a sustained feature of classroom practice, replacing less effective teaching strategies. When this is done successfully, they become a part of the school’s and teacher’s educational DNA. To do this we are talking about affecting the hearts and minds of educators. In so doing, we are impacting the very beliefs of those that will be delivering the innovation.

Affecting the hearts and minds of educators

Teachers are proud, and they are knowledgeable. They are also not easily influenced, and to be honest, who can blame them? Having experienced a succession of change initiatives throughout their careers, teachers are often sceptical, and it is naive of us not to acknowledge, and account for this systemically. They have usually seen it all before; something new comes on the radar, systems and leaders get excited, they then rush back to implement the new strategy by providing resourcing and making a strong case for the innovation. However, more often than not there is little real change to teaching practice or student learning outcomes.

The question has to be asked by leaders, and schools more broadly; ‘Why didn’t we get traction?’ It is not to say that teachers, or leaders for that matter, do not have the best interests for learners at heart. Instead, we need to consider the nature of improvement, and acknowledge that the improvement cycle that has been engaged with may be missing a crucial element.

Through her research, Robinson has discovered that leaders often do not take the time necessary to engage teachers’ mental model in relation to existing teaching strategies, strategies which teachers are highly invested in. Nor do they take the time to explain their own beliefs around the newly identified teaching strategy that they believe will see improved student learning outcomes. If teachers are not thoroughly convinced that a new strategy will be more effective then what they already do, then what we find is that teachers revert to their previous mental model, and the beliefs and teaching strategies that engaged it.

When this occurs, when teachers’ beliefs about what works best do not changed, improved student learning outcomes are unlikely, and the chance to innovate is lost. This is a critical tipping point in reaching commitment to any teaching innovation, and it is this element that is missed in most improvement cycles. Aware of the importance of commitment within any improvement cycle if it is to lead to improved learning outcomes, I have developed the Deep Beliefs Dialogic Protocol to guide leaders as they acknowledge and positively influence teachers’ mental models.

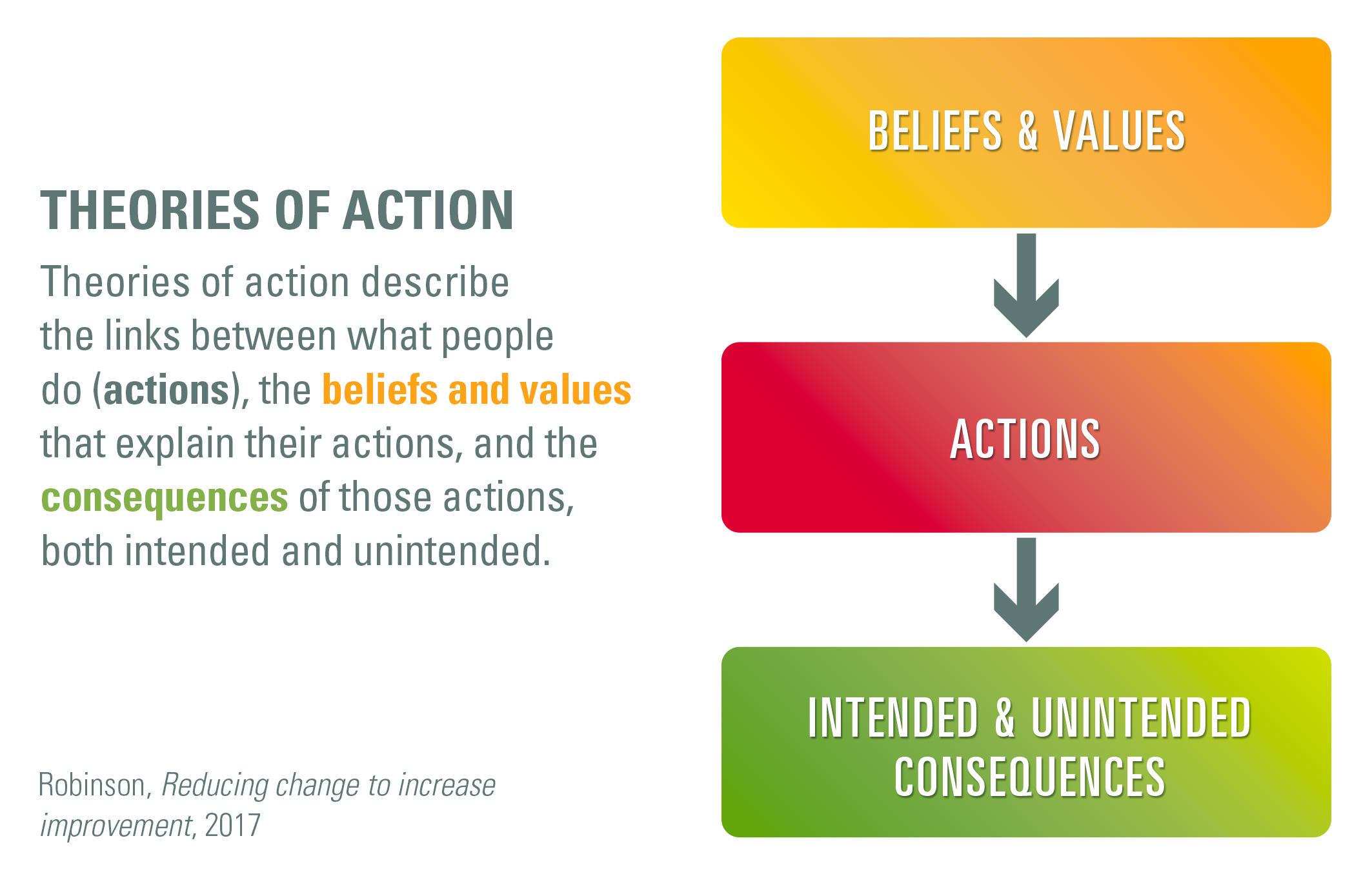

The infographic below, Theories of Action, provides a clear insight into the foundational role beliefs and values play in how teachers teach, and the subsequent achievement, or not, of sustained and improved student learning outcomes. Without impacting on teacher beliefs and values, any change is unlikely to be sustained.

Let’s unpack this further. No doubt you have been very busy in the pursuit of improvement; you did the research, you talked with peers, you met with staff, everyone engaged in professional learning, and yet, you do not see improved student learning outcomes. What we have in this situation, and it is common, is the difference between espoused theory and action. This occurs when innovative teaching practice does not transition from theory to practice. Put simply, teachers’ mental models have not changed; they do not believe in the merit of the new teaching strategy when compared to what they already do.

So, how do you influence a teacher’s theory of action? Some early questions to be considered by school communities when pursuing teaching innovation that leads to improved student learning outcomes include:

- What exactly is it that needs improving? Do you have enough evidence to be clear? (Data analysis plays a significant role here.)

- Why does it need improving? How is the current situation unacceptable? (This question helps clarify the challenge of practice)

- What are the school-based factors that have contributed to the current lack of success? What is our current teaching practice?

- How will the new teaching innovations address these factors?

Most important at this point in your improvement cycle is that all those who will be a part of the intended teaching innovation are genuine contributors throughout the process.

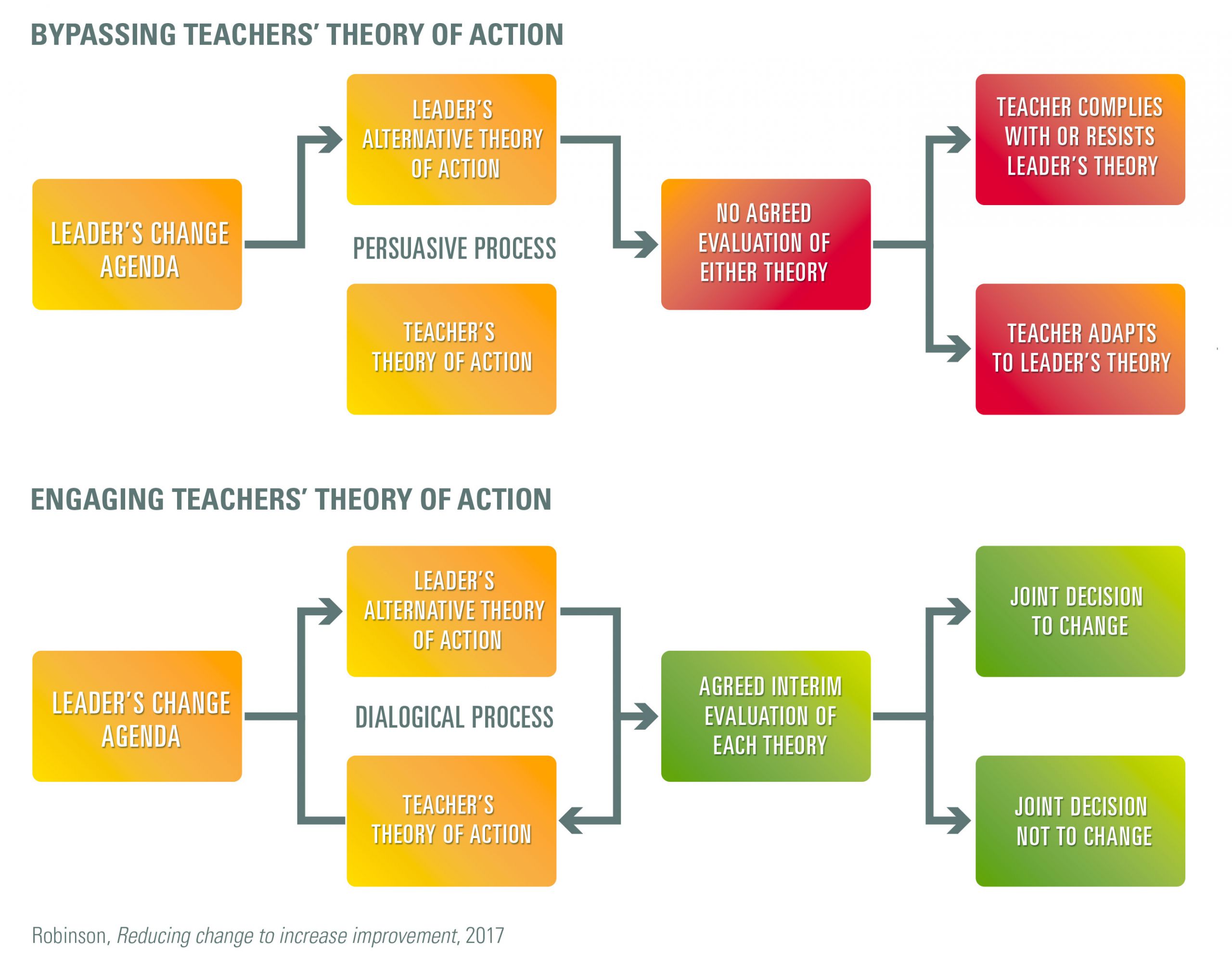

The first flow chart, Bypass teachers’ theory of action, represents the typical improvement process followed by schools. As you can see, dialogue that engages teachers’ beliefs and values about both old and new practice, and the desired agreement that comes from rich collaboration, is not present. The second flow chart, Engaging teachers’ theory of action, invests in the dialogic process until there is understanding, agreement and commitment.

A dialogic process that engages leader’s and teacher’s theory of action requires:

- leader and teacher inquiry into the practices they want to change, and the discovery of the theories of action (refer to the Theories of Actions infographic, pg. 2) that explains and sustains them

- a series of dialogic, data-informed conversations, that identifies why the current practice requires improvement, and introduces the alternative practice that is being proposed. Where tension between the old and new mental models exists, this must be resolved

- teachers agreeing that they have understood both current and future practices, before comparing the relative merit of what is being proposed compared to what is currently happening

- an agreement that the proposed future practice is worth trying

Ultimately, the key to success is that all participants say what they believe, and to do this, they must be confident that they will not be judged. Without this confidence, and the relational trust that underpins it, all we will see is early compliance, which translates to doors closed to the possibilities of innovation, and the same level of student learning outcomes that brought about the need for improvement in the first place. (To read more about relational trust and collective teacher efficacy see pervious posts in this category)

Robinson leaves us with a timely reminder, “Perhaps my key message is that the path to improvement lies in deep and respectful inquiry into the practices you want to change.”

To learn more about engaging your staffs’ mental models through our Deep Beliefs Dialogic Protocol, or anything else that has been covered, please do not hesitate to make contact. It may well make the difference you have been searching for.

Have a question for Travis, or need more info? Let’s chat.

Under no obligation, our preference is to spend time with you prior to delivering professional learning for teachers, or tailored leadership guidance, so that the partnership we develop is unique to your school.

When pursuing PROGRESS FOR ALL, All of the time, we believe time spent planning is time well spent.